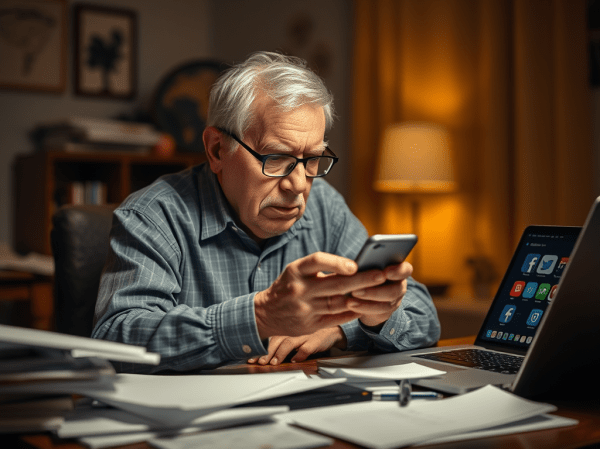

It happened to me last Thursday. I was tired, I was jet lagged and I was feeling like garbage. My defenses were down. So, before I realized it, I was spinning down a social media sewer spiral. My thumb took over, doom scrolling through post after post offering very biased commentary on the current state of the world, each reinforcing just how awful things are. Little was offered in the way of factual back up, and I didn’t bother looking for it. My mood plummeted. I alternated between paranoia, outrage and depression. An hour flew by as my brain was hijacked by a feckless feed.

And I know better. I really do. Up in my prefrontal cortex, I knew I was being sucked into a vicious vortex of AI slop and troll baiting. Each time I scrolled down, I would tell myself, “Okay, this is the last one. After this, put the phone down.” And each time, my thumb would ignore me.

This is not news to any of us. Every one of you reading this knows about the addictive nature of social media. And you also know the pernicious impacts of AI generated content spoon fed to us by an algorithm whose sole purpose is to hog tie our own willpower and keep our eyes locked on the screen. I also suspect that you, like I, think because we know all this, we have built up at least some immunity to the siren call of social media.

But I’m here to tell you that social media has gotten really, really good at being really, really awful for us. I didn’t notice it so much when I was on my game, busy doing other things and directing my attention with a fully functional executive brain. But the minute my guard slipped, the minute my cognitive capacity shifted down into a lower gear, I was sucked into the misinformational sh*thole that is social media.

Being a guy that likes to ask why, I did exactly that when the jet lag finally dissipated. Why did I, a person who should know better, fall into the crappy content trap? “Maybe,” I said to myself reluctantly, “it’s a generational thing.” Maybe brains of a certain age are more susceptible to being cognitively hijacked and led astray.

A recent study from the University of Utah does lend some credence to that theory. Researchers found that adults older than 60 were more likely to share misinformation online than younger people. This was true for information about health, but a prior study showed an even higher tendency to swallow bad information when it came to politics.

Lead researcher Ben Lyons set out to find why those of us north of 60 are more likely to be led astray by online misinformation. Spoiler alert – it doesn’t have anything to do with our brains slowing down or lower information literacy rates. It appears that older people can sniff out bullshit just as well as younger people. But it turns out that if that information, no matter how dubious it is, matches our own beliefs and world view, we’ll happily share it even if it doesn’t pass the smell test.

Lyons called this congeniality bias. I’ve talked before about the sensemaking cycle. In it, new information is matched to our existing belief schema. It it’s a match, we usually accept it without a lot of qualification. If it isn’t, we can choose to reject it or we can reframe our beliefs based on the new information. The second option is a lot more work and, it seems, the older we get the less likely we are to do this heavy lifting. As we age, we get more fully locked into who we are and what we believe. We’ve spent a lot of years building our beliefs and so we’re reluctant to stray from them.

Of course, like all things human, this tendency is not a given nor universally applied. Some older people are naturally more skeptical, and some are more inflexible in their beliefs. Not surprisingly, Lyons found those that leaned right in their political affiliations tend to be more belief-bound.

But, as I discovered this past Thursday, these information filtering tendencies are dependent on our moods and cognitive capacity. I am a naturally skeptical person and like to think I’m usually pretty picky about my information sources. But this is true only when I’m on my game. The minute my brain down-shifted, I began accepting dubious information at face value simply because I happened to agree with it. I didn’t bother checking to make sure it was true.

It sounded true, and that was all that mattered.