A few items on my recent to-do list have necessitated dealing with multiple levels of governmental bureaucracy: regional, provincial (this being in Canada) and federal. All three experiences were, without exception, a complete pain in the ass. So, having spent a good part of my life advising companies on how to improve their customer experience, the question that kept bubbling up in my brain was, “Why the hell is dealing with government such a horrendous experience?”

Anecdotally, I know everyone I know feels the same way. But what about everyone I don’t know? Do they also feel that the experience of dealing with a government agency is on par with having a root canal or colonoscopy?

According to a survey conducted last year by the research firm Qualtrics XM, the answer appears to be yes. This report paints a pretty grim picture. Satisfaction with government services ranked dead last when compared to private sector industries.

The next question, being that AI is all I seem to have been writing about lately, is this: “Could AI make dealing with the government a little less awful?”

And before you say it, yes, I realize I recently took a swipe at the AI-empowered customer service used by my local telco. But when the bar is set as low as it is for government customer service, I have to believe that even with the limitations of artificially intelligent customer service as it currently exists, it would still be a step forward. At least the word “intelligent” is in there somewhere.

But before I dive into ways to potentially solve the problem, we should spend a little time exploring the root causes of crappy customer service in government.

First of all, government has no competitors. That means there are no market forces driving improvement. If I have to get a building permit or renew my driver’s license, I have one option available. I can’t go down the street and deal with “Government Agency B.”

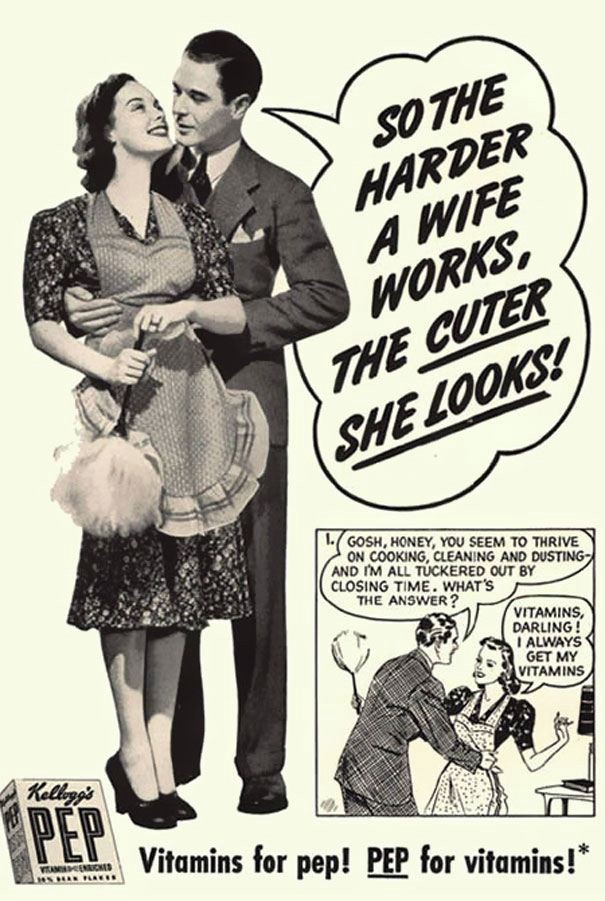

Secondly, in private enterprise, the maxim is that the customer is always right. This is, of course, bullshit. The real truth is that profit is always right, but with customers and profitability so inextricably linked, things generally work out pretty well for the customer.

The same is not true when dealing with the government. Their job is to make sure things are (supposedly) fair and equitable for all constituents. And the determination of fairness needs to follow a universally understood protocol. The result of this is that government agencies are relentlessly regulation bound and fixated on policies and process, even if those are hopelessly archaic. Part of this is to make sure that the rules are followed, but let’s face it, the bigger motivator here is to make sure all bureaucratic asses are covered.

Finally, there is a weird hierarchy that exists in government agencies. Frontline people tend to stay in place even if governments change. But the same is often not true for their senior management. Those tend to shift as governments come and go. According to the Qualtrics study cited earlier, less than half (48%) of government employees feel their leadership is responsive to feedback from employees. About the same number (47%) feel that senior leadership values diverse perspectives.

This creates a workplace where most of the people dealing with clients feel unheard, disempowered and frustrated. This frustration can’t help but seep across the counter separating them from the people they’re trying to help.

I think all these things are givens and are unlikely to change in my lifetime. Still, perhaps AI could be used to help us navigate the serpentine landscape of government rules and regulations.

Let me give you one example from my own experience. I have to move a retaining wall that happens to front on a lake. In Canada, almost all lake foreshores are Crown land, which means you need to deal with the government to access them.

I have now been bouncing back and forth between three provincial ministries for almost two years to try to get a permit to do the work. In that time, I have lost count of how many people I’ve had to deal with. Just last week, someone sent me a couple of user guides that “I should refer to” in order to help push the process forward. One of them is 29 pages long. The other is 42 pages. They are both about as compelling and easy to understand as you would imagine a government document would be. After a quick glance, I figured out that only two of the 71 combined pages are relevant to me.

As I worked my way through them, I thought, “surely some kind of ChatGPT interface would make this easier, digging through the reams of regulation to surface the answers I was looking for. Perhaps it could even guide you through the application process.”

Let me tell you, it takes a lot to make me long for an AI-powered interface. But apparently, dealing with any level of government is enough to push me over the edge.