If you choose to play in the social arena, you have to accept that the typical peaks and valleys of business success can suddenly become impossibly steep.

In social media networks, your brand message is whatever meme happens to emerge from the collective activity of this connected market. Marketers have little control — and sometimes, they have no control. At best, all they can do is react by throwing another carefully crafted meme into the social-sphere and hope it picks up some juice and is amplified through the network.

That’s exactly what happened to Peloton in the past week and a half.

On Dec. 9, the HBO Max sequel to “Sex and the City” killed off a major character — Chris Noth’s Mr. Big — by giving him a heart attack after his one thousandth Peloton ride. Apparently, HBO Max gave Peloton no advance warning of this branding back hand.

On Dec. 10, according to Axios, there was a dramatic spike in social interactions talking about Mr. Big’s last ride, peaking near 80 thousand. As you can imagine, the buzz was not good for Peloton’s business.

On Dec. 12, Peloton struck back with its own ad, apparently produced in just 24 hours by Ryan Reynold’s Maximum Effort agency. This turned the tide of the social buzz. Again, according to data from Newswhip and Axios, social media mentions peaked. This time, they were much more positive toward the Peloton brand.

It should be all good — right? Not so fast. On Dec 16, two sexual assault allegations were made against Chris Noth, chronicled in The Hollywood Reporter. Peloton rapidly scrubbed its ad campaign. Again, the social sphere lit up and Peloton was forced back into defensive mode.

Now, you might call all this marketing froth, but that’s the way it is in our hyper-connected world. You just have to dance the dance — be nimble and respond.

But my point is not about the marketing side of this of this brouhaha – which has been covered to death, at least at MediaPost (sorry, pardon the pun.) I’m more interested in what happens to the people who have some real skin in this particular game, whose lives depend on the fortunes of the Peloton brand. Because all this froth does have some very IRL consequences.

Take Peloton’s share price, for one.

The day before the HBO show aired, Peloton’s shares were trading at $45.91. The next day, they tumbled 16%. to $38.51.

And that’s just one chapter in the ongoing story of Peloton’s stock performance, which has been a hyper-compressed roller coaster ride, with the pandemic and a huge amount of social media buzz keeping the foot firmly on the accelerator of stock performance through 2020, but then subsequently dropping like a rock for most of 2021. After peaking as high as $162 a share exactly a year ago, the share price is back down to spitting distance of its pre-pandemic levels.

Obviously, Peloton’s share price is not just dependent on the latest social media meme. There are business fundamentals to consider as well.

Still, you have to accept that a more connected meme-market is going to naturally accelerate the speed of business upticks and declines. Peloton signed up for this dance — and when you do that, you have to accept all that comes with it.

In terms of the real-world consequences of betting on the buzz, there are three “insider” groups (not including customers) that will be affected: the management, the shareholders and the employees. The first of these supposedly went into this with their eyes open. The second of these also made a choice. If they did their due diligence before buying the stock, they should have known what to expect. But it’s the last of these — the employees — that I really feel for.

With ultra-compressed business cycles like Peloton has experienced, it’s tough for employees to keep up. On the way up the peak, the company is running ragged trying to scale for hyper-growth. If you check employee review sites like Glassdoor.com, there are tales of creaky recruitment processes not being able to keep up. But at least the ride up is exciting. The ride down is something quite different.

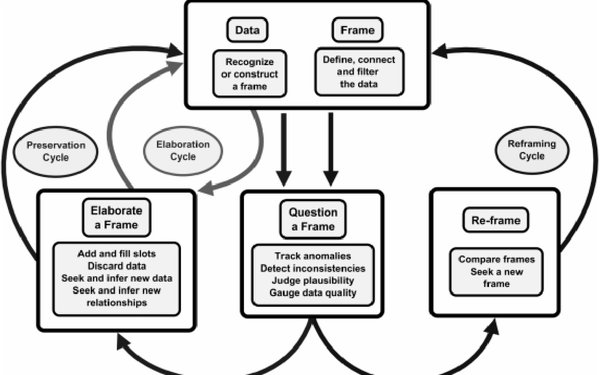

In psychological terms, there is something called the locus of control. These are the things you feel you have at least some degree of control over. And there is an ever-increasing body of evidence that shows that locus of control and employee job satisfaction are strongly correlated. No one likes to be the one constantly waiting for someone else to drop the other shoe. It just ramps up your job stress. Granted, job stress that comes with big promotions and generous options on a rocket ship stock can perhaps be justified. But stress that’s packaged with panicked downsizing and imminent layoffs is not a fun employment package for anyone.

That’s the current case at Peloton. On Nov. 5 it announced an immediate hiring freeze. And while there’s been no official announcement of layoffs that I could find, there have been rumors of such posted to the site thelayoff.com. This is not a fun environment for anyone to function in. Here’s what one post said: “I left Peloton a year ago when I realized it was morphing into the type of company I had no intention of working for.”

We have built a business environment that is highly vulnerable to buzz. And as Peloton has learned, what the buzz giveth, the buzz can also taketh away.