The inexact science of branding is nowhere more evident that in the case of the Tesla Cybertruck, which looks like it might usurp the Edsel’s title as the biggest automotive flop in history.

First, a little of the Tesla backstory. No, it wasn’t founded by Elon Musk. It was founded in 2003 by Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning. Musk came in a year later as a money man. Soon, he had forced Eberhard and Tarpenning out of the company. But their DNA remained, notably in the design and engineering of the hugely popular Tesla Model S, Model X and Model 3. These designs drove Tesla to capture over 50% of the electric car market and are straight line extensions of the original technology developed by Eberhard, Tarpenning and their initial team

Musk is often lauded as an eccentric genius in the mold of Steve Jobs, who had his fingers in every aspect of Tesla. While he was certainly influential, it’s not in the way most people think. The Model S, Model X and Model 3 soon became plagued by production issues, failed software updates, product quality red flags and continually failing to meet to meet Musk’s wildly optimistic and often delusional predictions, both in terms of sales and promised updates. Those things all happened on Musk’s watch. Even with all this, Tesla was the darling of investors and media, driving it to be the most valuable car company in the world.

Then came the Cybertruck.

Introduced in 2019, the Cybertruck did have Musk’s fingerprints all over it. The WTF design, the sheer impracticality of a truck in name only, a sticker price nearly double of what Musk originally promised and a host of quality issues including body panels that have a tendency to fall off have caused sales to not even come close to projections.

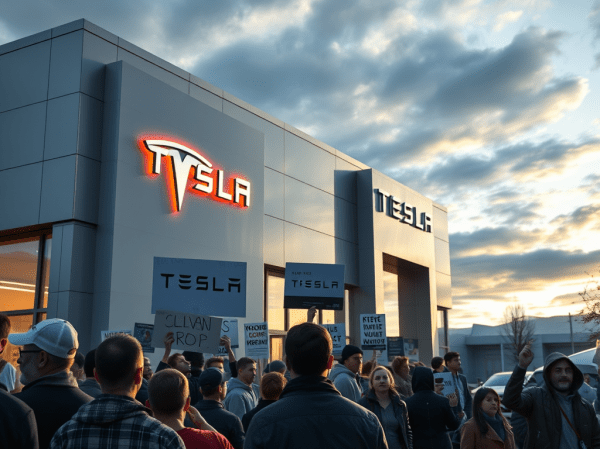

In its first year of sales (2024), the Cybertruck sold 40,000 units, about 16% of what Musk predicted annual sales could be. That makes it a bigger fail than the Edsel, which sold 63,000 units against a target of 200,000 sales in its introductory year – 1958. The Edsel did worse in 1959 and was yanked from the market in 1960. The Cybertruck is sinking even faster. In the first quarter of this year, only 6406 Cybertrucks were sold, half the number sold in the same quarter a year ago. There are over 10,000 Cybertrucks on Tesla lots in the U.S., waiting for buyers that have yet to show up.

But it’s not just that the Cybertruck is a flawed product. Musk has destroyed Tesla’s brand in a way that can only be marvelled at. His erratic actions have managed to generate feelings of visceral hate in a huge segment of the market and that hate has found a visible target in the Cybertruck. It has become the symbol of Elon Musk’s increasingly evident meltdown.

I remember my first reaction when I heard that Musk had jumped on the MAGA bandwagon. “How the hell,” I thought, “does that square with the Tesla brand?” That brand, pre-Musk-meltdown and pre-Cybertruck, was a car for the environmentally conscious who had a healthy bank account – excitingly leading edge but not dangerously so. Driving a Tesla made a statement that didn’t seem to be in the MAGA lexicon at all. It was all very confusing.

But I think it’s starting to make a little more sense. That brand was built by vehicles that Musk had limited influence over. Sure, he took full credit for the brand, but just like company he took over, it’s initial form and future direction was determined by others.

The Cybertruck was a different story. That was very much Musk’s baby. And just like his biological ones (14 and counting), it shows all the hallmarks of Musk’s “bull in a China shop” approach to life. He lurches from project to project, completely tone-deaf to the implications of his actions. He is convinced that his genius is infallible. If the Tesla brand is a reflection of Musk, then the Cybertruck gives us a much truer picture. It shows what Tesla would have been if there had never been a Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning and Musk was the original founder.

To say that the Cybertruck is “off brand” for Tesla is like saying that the Titanic had a tiny mishap. But it’s not that Musk made a mistake in his brand stewardship. It’s that he finally had the chance to build a brand that he believed in.