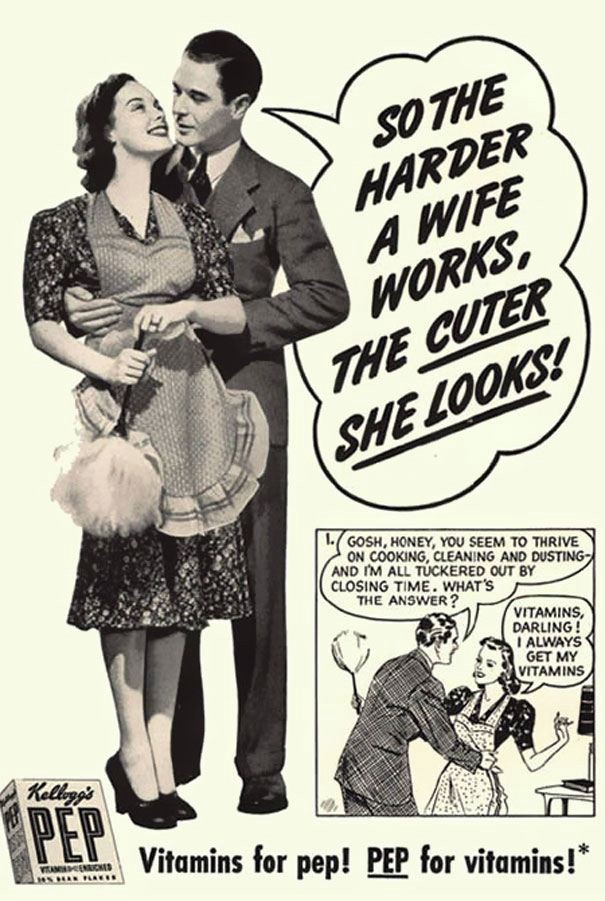

The Dove brand has just placed a substantial stake in the battleground over the use of AI in media. In a campaign called “Keep Beauty Real”, the brand released a 2-minute video showing how AI can create an unattainable and highly biased (read “white”) view of what beauty is.

If we’re talking branding strategy, this campaign in a master class. It’s totally on-brand with Dove, who introduced its “Campaign for Real Beauty” 18 years ago. Since then, the company has consistently fought digital manipulation of advertising images, promoted positive body image and reminded us that beauty can come in all shapes, sizes and colors. The video itself is brilliant. You really should take a couple minutes to see it if you haven’t already.

But what I found just as interesting is that Dove chose to use AI as a brand differentiator. The video starts with by telling us, “By 2025, artificial intelligence is predicted to generate 90% of online content” It wraps up with a promise: “Dove will never use AI to create or distort women’s images.”

This makes complete sense for Dove. It aligns perfectly with its brand. But it can only work because AI now has what psychologists call emotional valency. And that has a number of interesting implications for our future relationship with AI.

“Hot Button” Branding

Emotional valency is just a fancy way of saying that a thing means something to someone. The valence can be positive or negative. The term valence comes from the German word valenz, which means to bind. So, if something has valency, it’s carrying emotional baggage, either good or bad.

This is important because emotions allow us to — in the words of Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman — “think fast.” We make decisions without really thinking about them at all. It is the opposite of rational and objective thinking, or what Kahneman calls “thinking slow.”

Brands are all about emotional valency. The whole point of branding is to create a positive valence attached to a brand. Marketers don’t want consumers to think. They just want them to feel something positive when they hear or see the brand.

So for Dove to pick AI as an emotional hot button to attach to its brand, it must believe that the negative valence of AI will add to the positive valence of the Dove brand. That’s how branding mathematics sometimes work: a negative added to a positive may not equal zero, but may equal 2 — or more. Dove is gambling that with its target audience, the math will work as intended.

I have nothing against Dove, as I think the points it raises about AI are valid — but here’s the issue I have with using AI as a brand reference point: It reduces a very complex issue to a knee-jerk reaction. We need to be thinking more about AI, not less. The consumer marketplace is not the right place to have a debate on AI. It will become an emotional pissing match, not an intellectually informed analysis. And to explain why I feel this way, I’ll use another example: GMOs.

How Do You Feel About GMOs?

If you walk down the produce or meat aisle of any grocery store, I guarantee you’re going to see a “GMO-Free” label. You’ll probably see several. This is another example of squeezing a complex issue into an emotional hot button in order to sell more stuff.

As soon as I mentioned GMO, you had a reaction to it, and it was probably negative. But how much do you really know about GMO foods? Did you know that GMO stands for “genetically modified organisms”? I didn’t, until I just looked it up now. Did you know that you almost certainly eat foods that contain GMOs, even if you try to avoid them? If you eat anything with sugar harvested from sugar beets, you’re eating GMOs. And over 90% of all canola, corn and soybeans items are GMOs.

Further, did you know that genetic modifications make plants more resistance to disease, more stable for storage and more likely to grow in marginal agricultural areas? If it wasn’t for GMOs, a significant portion of the world’s population would have starved by now. A 2022 study suggests that GMO foods could even slow climate change by reducing greenhouse gases.

If you do your research on GMOs — if you “think slow’ about them — you’ll realize that there is a lot to think about, both good and bad. For all the positives I mentioned before, there are at least an equal number of troubling things about GMOs. There is no easy answer to the question, “Are GMOs good or bad?”

But by bringing GMOs into the consumer world, marketers have shut that down that debate. They are telling you, “GMOs are bad. And even though you consume GMOs by the shovelful without even realizing it, we’re going to slap some GMO-free labels on things so you will buy them and feel good about saving yourself and the planet.”

AI appears to be headed down the same path. And if GMOs are complex, AI is exponentially more so. Yes, there are things about AI we should be concerned about. But there are also things we should be excited about. AI will be instrumental in tackling the many issues we currently face.

I can’t help worrying when complex issues like AI and GMOs are broad-stroked by the same brush, especially when that brush is in the hands of a marketer.

Feature image: Body Scan 002 by Ignotus the Mage, used under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 / Unmodified