In the last post, I reviewed the various versions of the Technology Acceptance Model. Today, I’d like to introduce my own thoughts on the subject and a proposed new model. But first, I’d like to introduce an entirely new model to the discussion.

Introduction of Sense Making

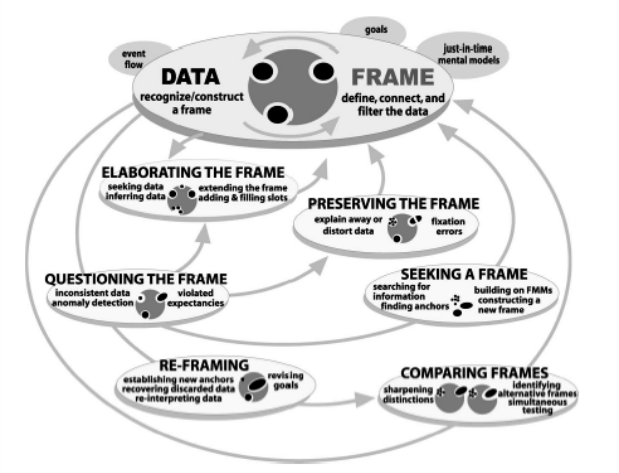

I like Gary Klein’s Theory of Sense Making – a lot! And in the area of technology acceptance, I think it has to be part of the discussion. It introduces a natural Bayesian rhythm to the process that I think provides a intuitive foundation for our decisions on whether or not we’ll accept a new technology.

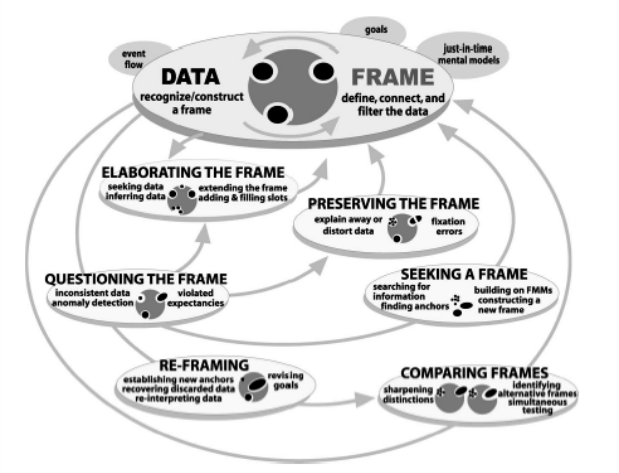

Gary Klein et al – Sensemaking Model How Might “Transformational” Technologies and Concepts be Barriers to Sensemaking in Intelligence Analysis

Essentially, the Sense Making Model says that when we try to make sense of something new, we begin with some type of perspective, belief or viewpoint. In Bayesian terms, this would be our prior. In Klein’s model, he called it a frame.

Now, this frame doesn’t only give us a context in which to absorb new data, it actually helps define what counts as data. This is a critical concept to remember, because it dramatically impacts everything that follows. Imagine, for example, that you arrive on the scene of a car accident. If your frame was that of a non-involved bystander, the data you might seek in making sense of the situation would be significantly different than if your frame was that of a person who recognized one of the vehicles involved as belonging to your next-door neighbor.

In the case of technology acceptance, this initial frame will shape what types of data we would seek in order to further qualify our decision. If we start with a primarily negative attitude, we would probably seek data that would confirm our negative bias. The opposite would be true if we were enthusiastic about the adoption of technology. For this reason, I believe the creation of this frame should be a step in any proposed acceptance model.

But Sense Making also introduces the concept of iterative reasoning. After we create our frame, we do a kind of heuristic “gap analysis” on our frame. We prod and poke to see where the weaknesses are. What are the gaps in our current knowledge? Are there inconsistencies in the frame? What is our level of conviction on our current views and attitudes? The weaker the frame, the greater our need to seek new data to strengthen it. This process happens without a lot of conscious consideration. For most of us, this testing of the frame is probably a subconscious evaluation that then creates an emotional valence that will impact future behavior. On one extreme, it could be a strongly held conviction, on the other it would be a high degree of uncertainty.

If we decide we need more data, the Sense Making Model introduces another “Go/No Go” decision point. If the new data confirms our initial frame, we elaborate that frame, making it more complete. We fill in gaps, strengthen beliefs, discard non-aligned data and update our frame. If our sense making is in support of a potential action and we seem to be heading in the right direction with our data foraging, this can be an iterative process that continually updates our frame until it’s strong enough to push us over the threshold of executing that action.

But, if the new data causes serious doubt about our initial frame, we may need to consider “reframing,” in which case we’d have to seek new frames, compare against our existing one and potentially discard it in favor of one of the new alternatives. This essentially returns us to square one, where we need to find data to elaborate the new frame. And there the cycle starts again.

This double loop learning process illustrates that a decision process, such as accepting a new technology, can loop back on itself at any point, and may do so at several points. More than this, it is always susceptible to a “reframing” incident, where new data may cause the existing frame to be totally discarded, effectively derailing the acceptance process.

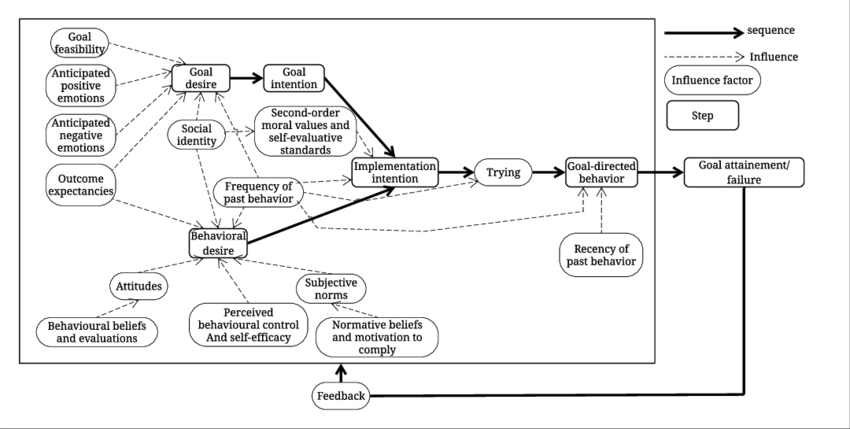

Revisiting Goal Striving

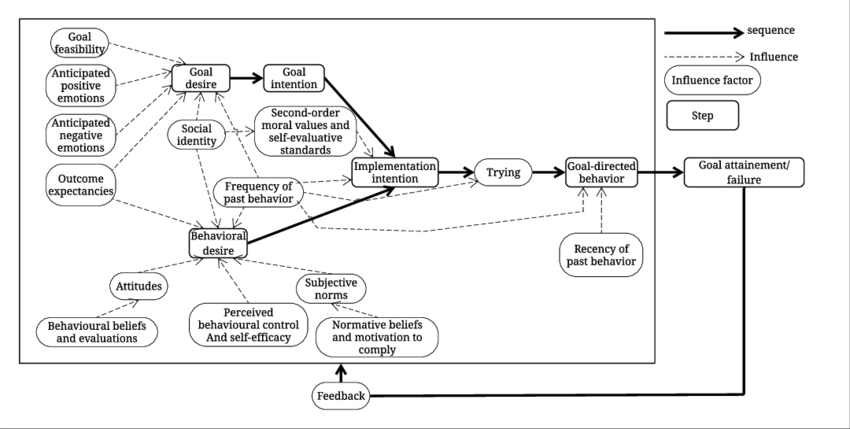

I also like Bagozzi’s Goal Striving model, for reasons outlined in a previous post. I won’t rehash them here, except to say that this model introduces a broader context that is more aligned with the complexity of our typical decision process. In this case, our desire to achieve goals is a fundamental part of the creation of the original frame, which forms the starting point for our technology acceptance decision. In this case, the Goal Desire step, at the left side of the model, could effectively be the frame that then gets updated as we move from Goal Intention to Behavioral Desire and then once again as we move to Behavioral Intention. All the inputs shown in Bagozzi’s model, shown as both external factors (ie Group Norms) and internal factors (Emotions, etc) would serve as data in either the updating or reframing loops in Klein’s model.

A New Model

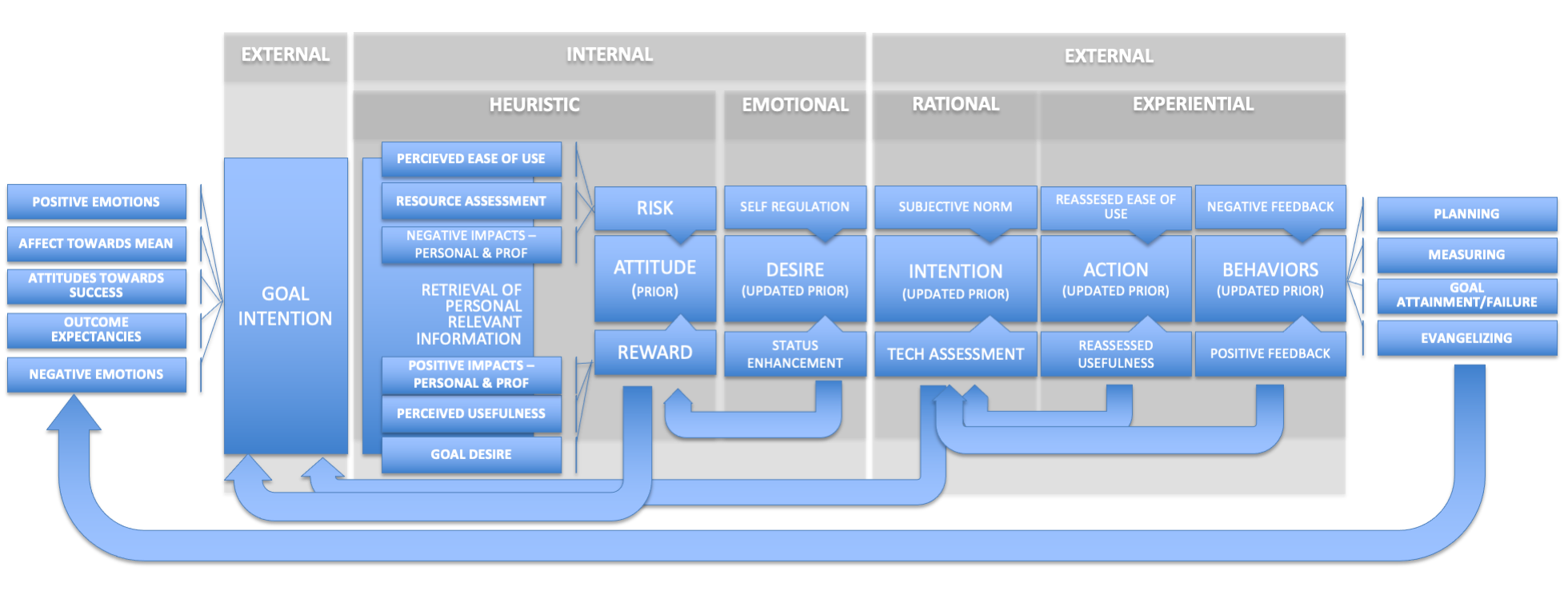

As the final step in this rather long process I’ve been dragging you through for the last several posts, I put forward a new proposed model for technology acceptance.

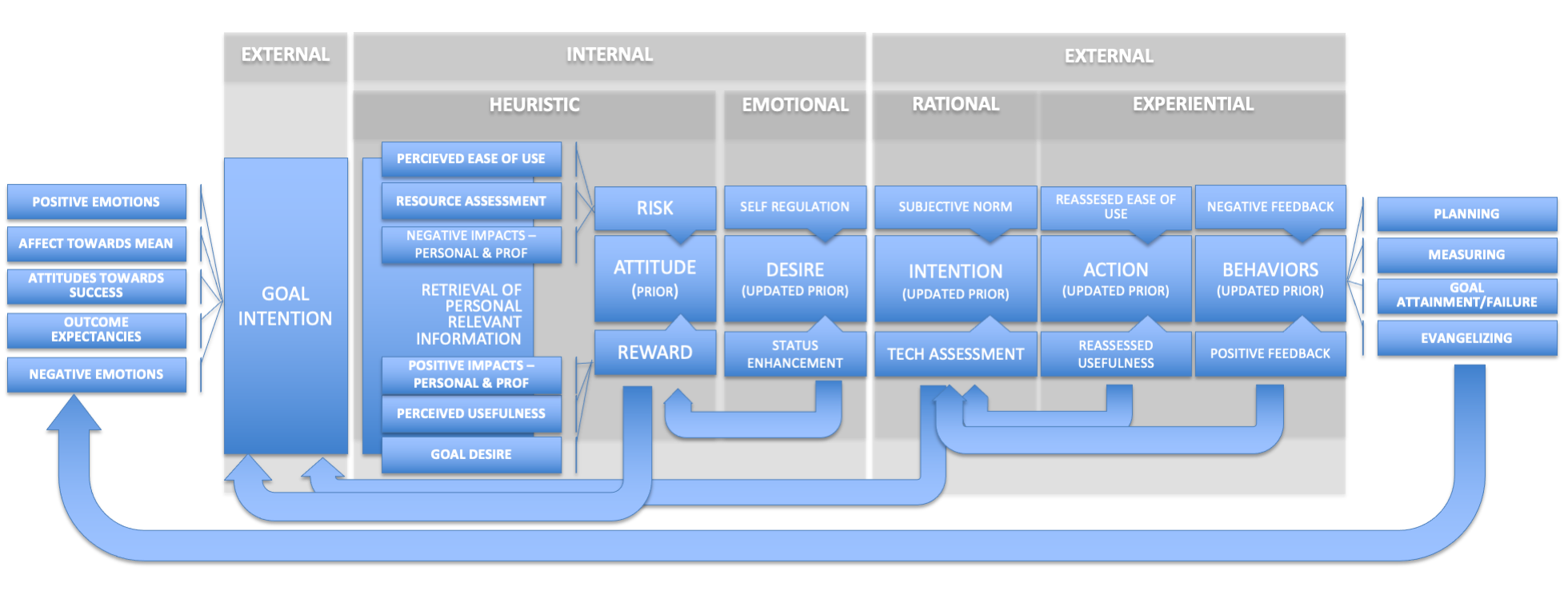

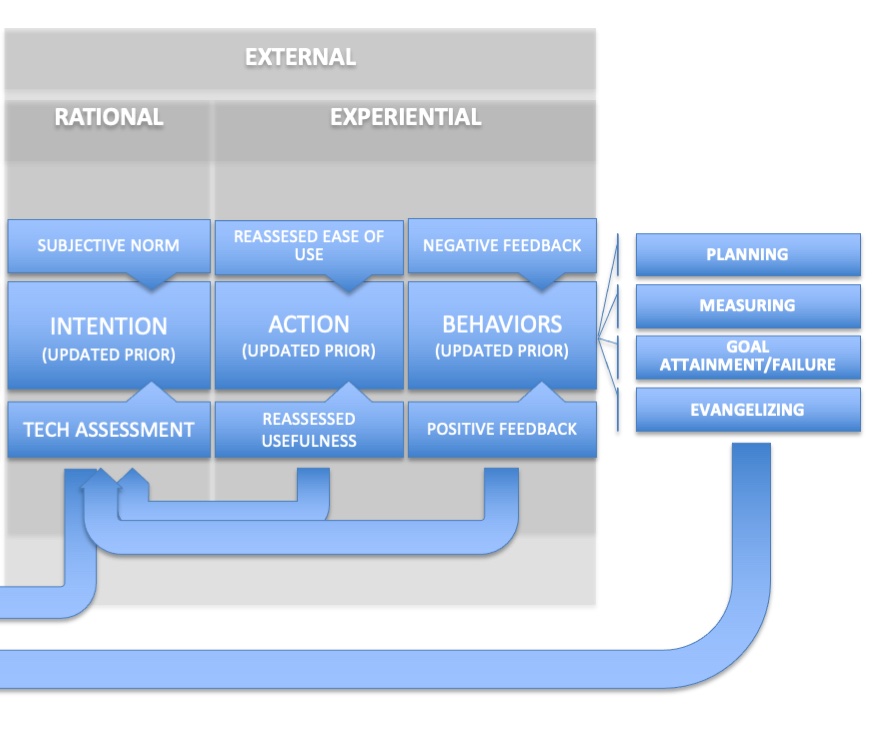

I’ve attempted to include elements of Sense Making, Goal Striving and some of the more valuable elements from the original Technology Acceptance Models. I’ve also tried to show that this in an iterative journey – a series of data gathering and consideration steps, each one of which can result in either a decision to move forward (elaborate the frame) or move backwards to a previous step (reframe a frame). The entire model is shown below, but we’ll break it down into pieces to explore each step a little more deeply.

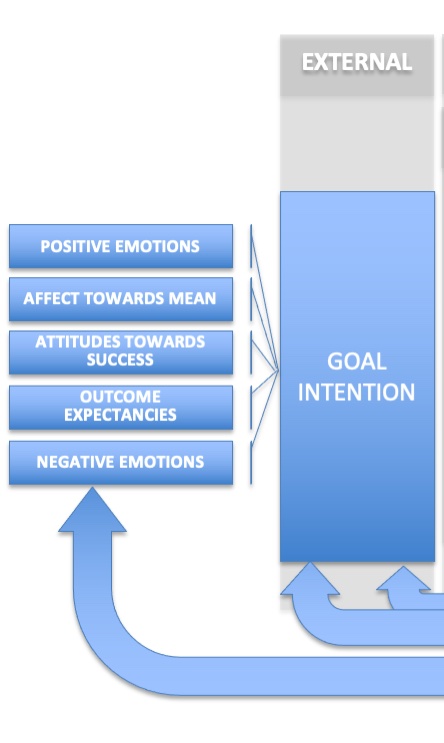

Setting the Frame

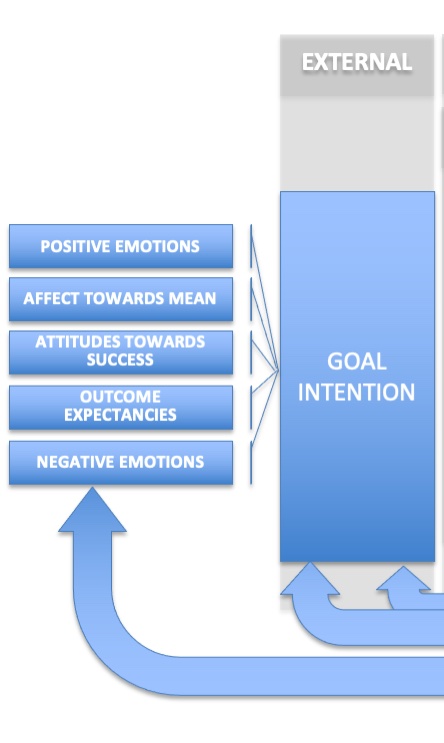

The first step is to set the original frame, which is the Goal Intention. In this case, a goal is either presented to us, or we set the goal ourselves. The setting of this goal is the trigger to establish both a cognitive and emotional frame that sets the context for everything that follows. Factors that go into the creation of the Goal Intention can include both positive and negative emotions, our attitudes towards the success of the goal, how it will impact our current situation (affect towards the mean), and what we expect as far as outcomes. These factors will determine how robust our Goal Intention is, which will factor heavily in any subsequent decisions that are made as part of this Goal Intention, including the decision to accept or reject any relevant technologies required to execute on our Goal Intention.

We can assume, because there is not an updating step shown here, that once the Goal Intention is formed, the person will move forward to the next step – the retrieval of internal information and the creation of our attitude towards the Goal to be achieved.

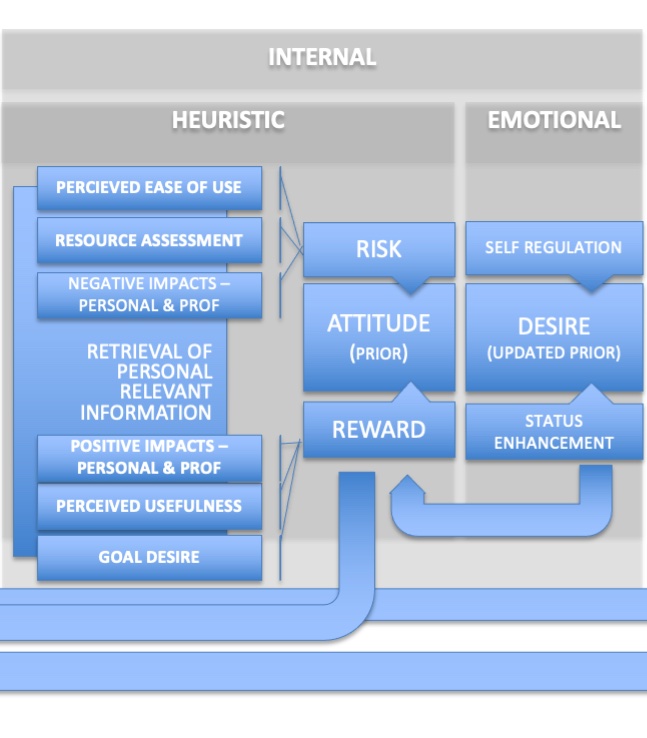

The Internal Update

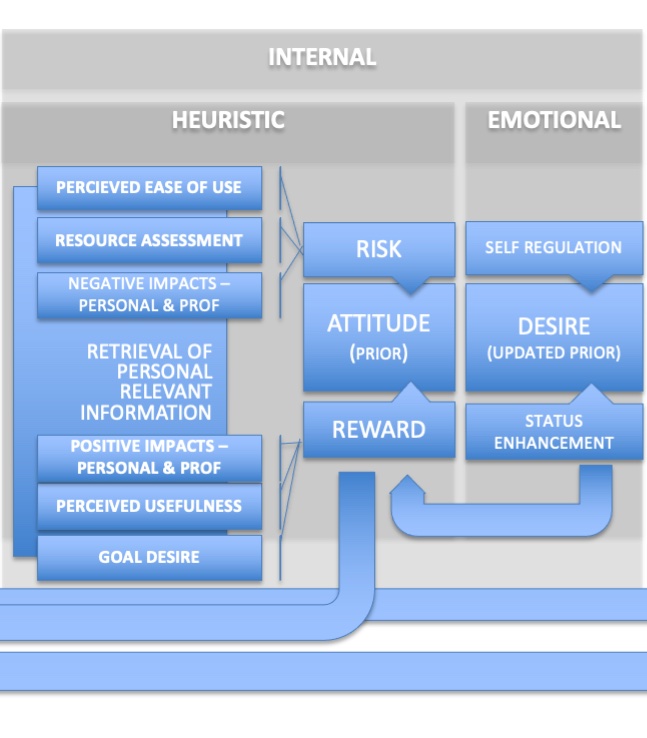

With the setting of the goal intention, we have our frame. Now, it’s up to us to update that frame. Again, our confidence in this initial frame will determine how much data we feel we need to connect to update our frame. This follows Herbert Simon’s heuristic rules of thumb for Bounded Rationality. If we’re highly confident in our frame (to the point where it’s entrenched as a belief) we’ll seek little or no data, and if we do, the data we seek will tend to be confirmatory. If we’re less confident in our frame, we’ll actively go and forage for more data, and we’ll probably be more objective in our judgement of that data. Again, remember, Klein’s Sense Making model says that our frame determines what we define as data.

The first update will be a heuristic and largely subconscious one. We’ll retrieve any relevant information from our own memory. This information, which may be positive or negative in nature, will be assembled into an “attitude” towards the technology. This is our first real conscious evaluation of the technology in question. This would be akin to a Bayesian “prior” – a starting point for subsequent evaluation. It also represents an updating of the original frame. We’ve moved from Goal Intention to a emotional judgement of the technology to be evaluated.

The creation of the “Attitude” also requires us to begin the Risk/Reward balancing, similar to Charnov’s Marginal Value Theorem used in optimal foraging. Negative items we retrieve increase risk, positive ones increase reward. The balance between the two determine our next action. From this point forward, each updating of the frame leads us to a new decision point. At this decision point, we have to decide whether we move forward (elaborate our frame) or return to an earlier point in the decision process, with the possibility that we may need to reframe at that point. Each of these represents a “friction point” in the decision process, with reward driving the process forward and risk introducing new friction. At the attitude state, excessive risk may cause us to go all the way back to reconsidering the goal intention. Does the goal as we understand it still seem like the best path forward, given the degree of risk we have now assigned to the execution of that goal?

Let’s assume we’ve decided to move forward. Now we have to take that Attitude and translate it into Desire. Desire brings social aspects into the decision. Will the adoption of the technology elevate our social status? Will it cause us to undertake actions that may not fit into the social norms of the organization, or square well with our own social ethics? These factors will have a moderating effect on our desire. Even if we agree that the technology in question may meet the goal, our desire may flag because of the social costs that go along with the adoption decision. Again, this represents a friction point, where our desire may be enough to carry us forward, or where it may not be strong enough, causing us to re-evaluate our attitude towards the technology. If we bump back to the “Attitude” stage, a sufficiently negative judgement may in turn bump us even further back to goal intention.

The External Update

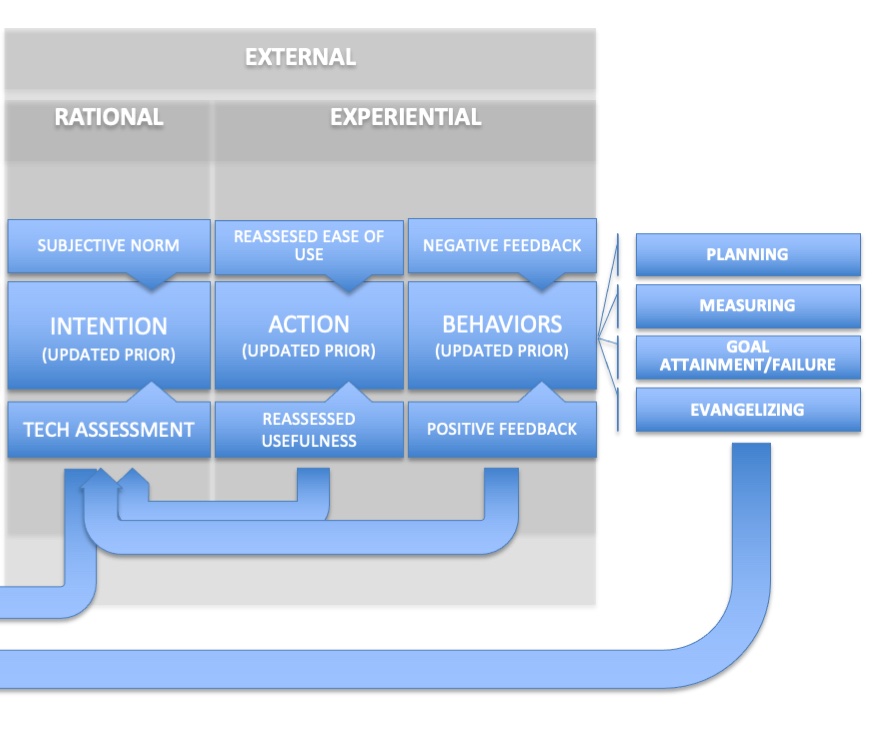

With the next stage, we’ve moved from Desire to Intention. Up to now the process has been primarily internal and also primarily either emotional or heuristic. There has been little to no rational deliberation about whether or not to accept the technology in question. The frame that has been created to this point is an emotional and attitudinal frame.

But now, assuming that this frame is open to updating with more information, the process becomes more open to external variables and also to the input of data gathered for the express purpose of rational consideration. We start openly canvassing the opinions of others (subjective norm) and evaluating the technology based on predetermined factors. In the language of marketing, this is the consumer’s “consideration” stage. We know the next step is Action – where our intention becomes translated into behavior. In the previous TAM models, this step was a foregone conclusion. Here, however, we see that it’s actually another decision friction point. If the data we gather doesn’t support our intention, action will not result. We will loop back to Goal Intention and start looking for alternatives. At the very least, this one stage may loop back on itself, resulting in iterative cycles of setting new data criteria, gathering this data and pushing towards either a “go” or “no go” decision. Only when there is sufficient forward momentum will we move to action.

Here, at the Action stage, our evaluation will rely on experiential feedback. At this point, we resurrect the concepts of “Ease of Use” and “Perceived Usefulness” from previous versions of TAM. In this case, the Intention stage would have constructed an assumed “prior” for each of these – a heuristic assessment of how easy it will be to use the technology and also the usefulness of it. This then gets compared to our actual use of the technology. If the bar of our expectations is not met, the degree of friction increases, holding us back from repeating the action, which is required to entrench it as a behavior. This will be a Charnovian balancing act. If the usefulness is sufficient, we will put up with a shortfall in the perceived ease of use. On the flip side, no matter how easy the tool is to use, if it doesn’t deliver on our expectation of usefulness, it will get rejected. Too much friction at this point will result in a loop back to the Intention stage (where we may reassess our evaluation of the technology to see if the fault lies with us or with the tool) and will possibly cause a reversion all the way to our Goal Intention.

If our experience meets our expectation, repetition will begin to create an organizational behavior. At this stage, we move from trial usage to embedding the technology into our processes. At this point, organizational feedback becomes the key evaluative criterion. Even if we love the technology, sufficient negative feedback from the organization will cause us to re-evaluation our intention. Finally, if the technology being evaluated successfully navigates past this chain of decision points without becoming derailed, it becomes entrenched. We then evaluate if it successfully plays its part in our attainment of our goals. This brings up full circle, back to the beginning of the process.

Summing Up

The original goal of the Technology Acceptance Model was to provide a testable model to predict adoption. My goal is somewhat different, showing Technology Adoption as a series of Sense Making and Goal Attainment decisions, each offering the opportunity to move forward to the next stage or loop back to a previous stage. In extreme cases, it may result in outright rejection of the technology. As far as testing for predictability, this is not the parsimonious model envisioned by Venkatesh, but then again, I suspect parsimony was sacrificed even by the Venkatesh and contributing authors somewhere between the multiple revisions that were offered.

This is a model of Bayesian decision making, and I believe it could be applied to many considered decision scenarios. One could map most higher end consumer purchases on the same decision path. The value of the model is in understanding each stage of the decision path and the factors that both introduce risk related friction and reward related momentum. Ideally, it would be fascinating to start to identify representative risk/reward thresholds at each point, so factors can be rebalanced to achieve a successful outcome.

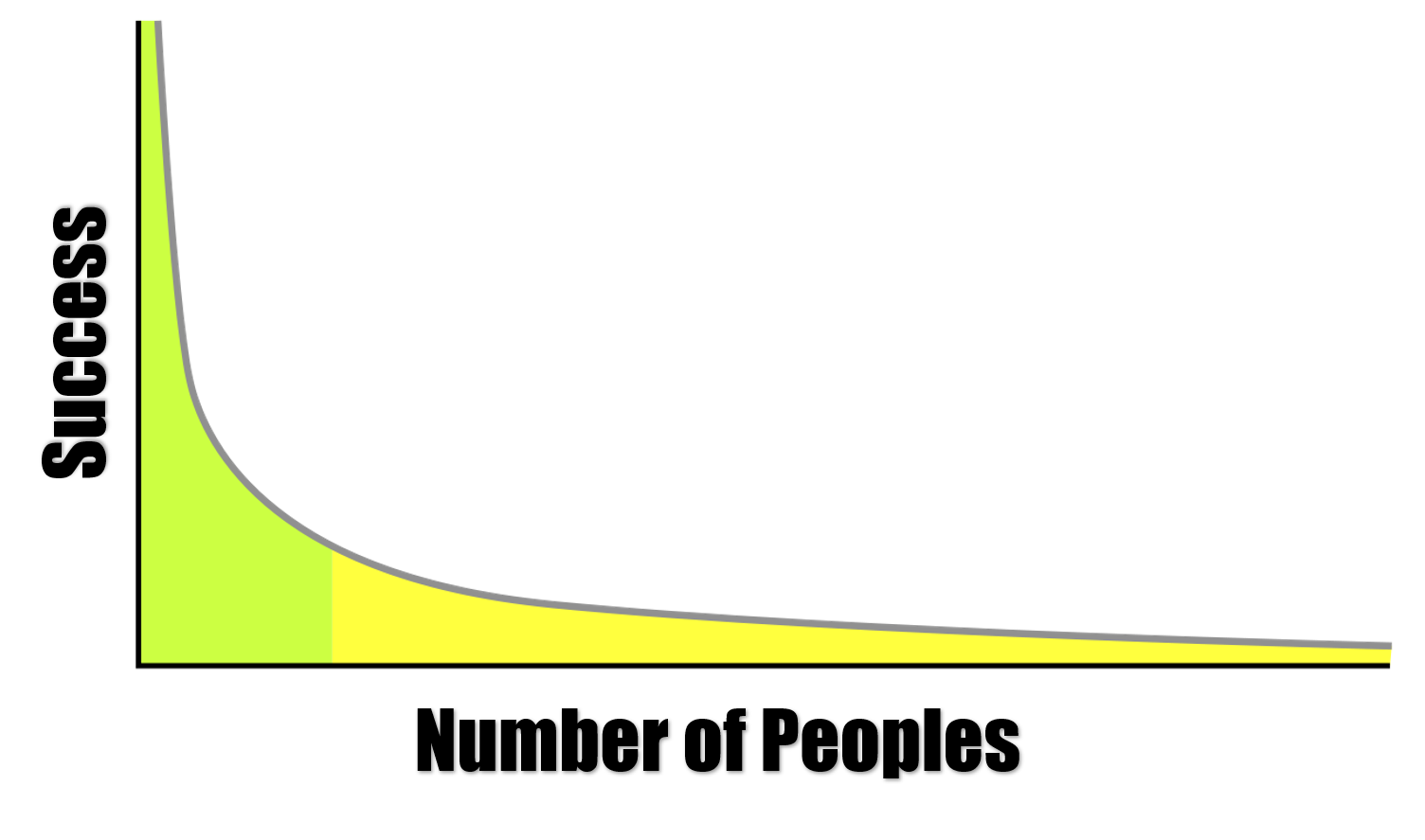

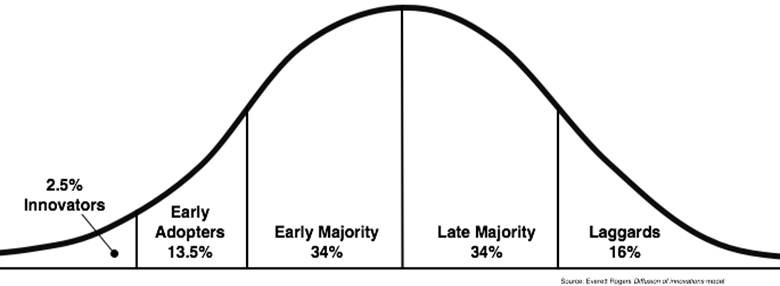

As we talk about the friction in these decision points, it’s also important to remember that we will all have different set points about how we balance risk and reward. When it comes to technology acceptance, our set point will determine where we fall on Everett Roger’s Diffusion of Technology distribution curve.

Those with a high tolerance for risk and an enhanced ability to envision reward will fall to the far left of the curve, either as Innovators or Early Adopters. Rogers noted in The Diffusion of Innovation:

Innovators may…possess a type of mental ability that better enables them to cope with uncertainty and to deal with abstractions. An innovator must be able to conceptualize relatively abstract information about innovations and apply this new information to his or her own situation

Those with a low tolerance for risk and an inability to envision rewards will be to the far right, falling into the Laggard category. The rest of us, representing 68% of the general population, will fall somewhere in between. So, in trying to predict the acceptance of any particular technology, it will be important to assess the innovativeness of the individual making the decision.

This hypothetical model represents a culmination of the behaviors I’ve observed in many B2B adoption decisions. I’ve always stressed the importance of understanding the risk/reward balance of your target customers. I’ve also mapped out how this can vary from role to role in organizational acceptance decisions.

This post, which is currently pushing 3000 words, is lengthy enough for today. In the next post, I’ll revisit what this new model might mean for our evaluation of usefulness and subsequent user loyalty.

It was interesting watching my family watch the Oscars Sunday night. Given that I’m the father of two millennials, who have paired with their own respective millennials, you can bet that it was a multi-screen affair. But to be fair, they weren’t the only ones splitting their attention amongst the TV and various mobile devices. I was also screen hopping.

It was interesting watching my family watch the Oscars Sunday night. Given that I’m the father of two millennials, who have paired with their own respective millennials, you can bet that it was a multi-screen affair. But to be fair, they weren’t the only ones splitting their attention amongst the TV and various mobile devices. I was also screen hopping.

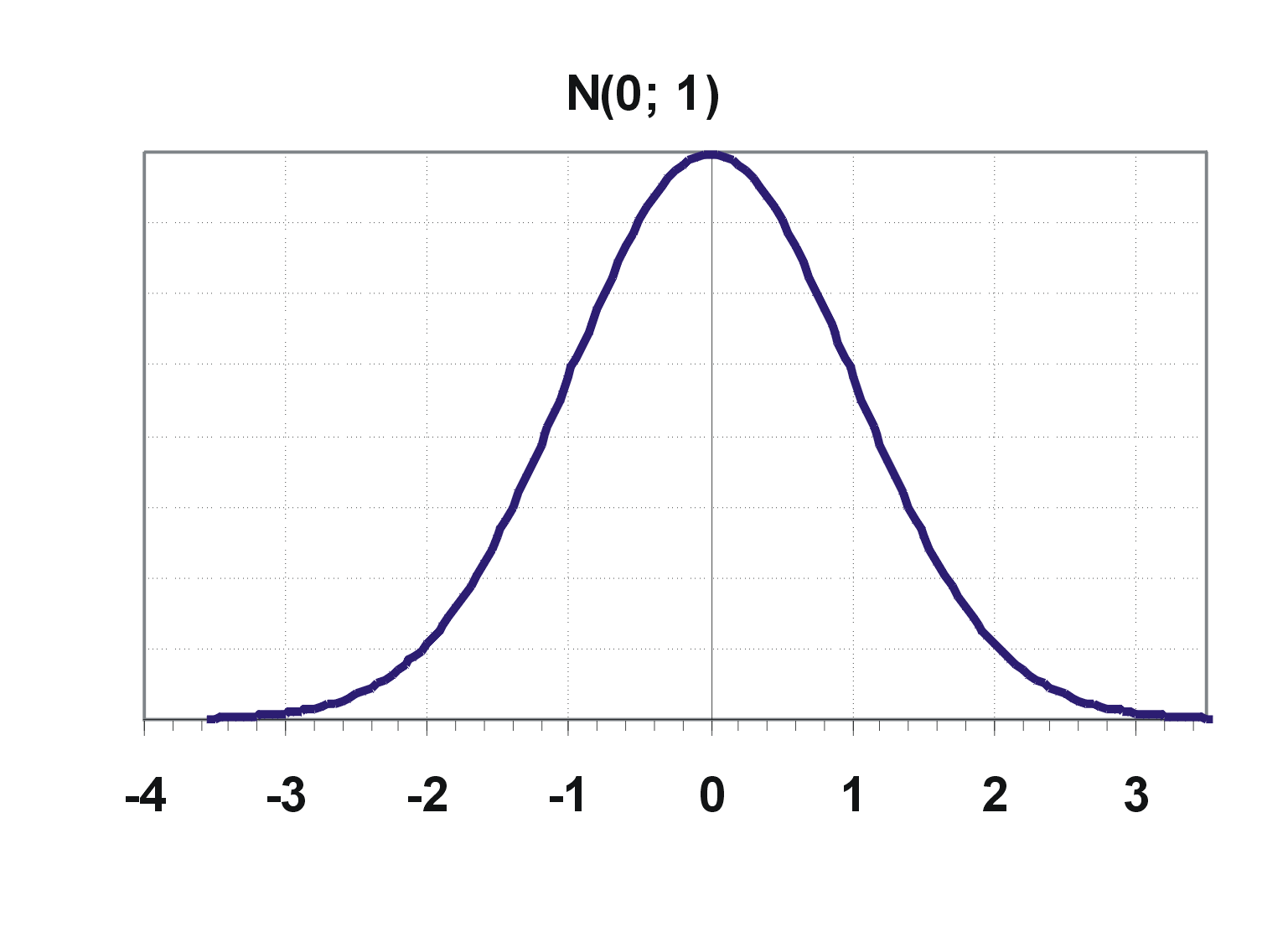

This variation typically plays out in a normal distribution curve, more commonly known as a bell curve. Most of us cluster towards the center – the norm. And as we move out from the center, venturing one or two standard deviations from the norm into outlier territory, our numbers drop dramatically.

This variation typically plays out in a normal distribution curve, more commonly known as a bell curve. Most of us cluster towards the center – the norm. And as we move out from the center, venturing one or two standard deviations from the norm into outlier territory, our numbers drop dramatically.