Willful ignorance is nothing new. Depending on your beliefs, you could say it was willful ignorance that got Adam and Eve kicked out of the Garden of Eden. But the visibility of it is higher than it’s ever been before. In the past couple of years, we have had a convergence of factors that has pushed willful ignorance to the surface — a perfect storm of fact denial.

Some of those effects include the social media effect, the erosion of traditional journalism and a global health crisis that has us all focusing on the same issue at the same time. The net result of all this is that we all have a very personal interest in the degree of ignorance prevalent in our society.

In one very twisted way, this may be a good thing. As I said, the willfully ignorant have always been with us. But we’ve always been able to shrug and move on, muttering “stupid is as stupid does.”

Now, however, the stakes are getting higher. Our world and society are at a point where willful ignorance can inflict some real and substantial damage. We need to take it seriously and we must start thinking about how to limit its impact.

So, for myself, I’m going to spend some time understanding willful ignorance. Feel free to come along for the ride!

It’s important to understand that willful ignorance is not the same as being stupid — or even just being ignorant, despite thousands of social media memes to the contrary.

Ignorance is one thing. It means we don’t know something. And sometimes, that’s not our fault. We don’t know what we don’t know. But willful ignorance is something very different. It is us choosing not to know something.

For example, I know many smart people who have chosen not to get vaccinated. Their reasons may vary. I suspect fear is a common denominator, and there is no shame in that. But rather than seek information to allay their fears, these folks have doubled down on beliefs based on little to no evidence. They have made a choice to ignore the information that is freely available.

And that’s doubly ironic, because the very same technology that enables willful ignorance has made more information available than ever before.

Willful ignorance is defined as “a decision in bad faith to avoid becoming informed about something so as to avoid having to make undesirable decisions that such information might prompt.”

And this is where the problem lies. The explosion of content has meant there is always information available to support any point of view. We also have the breakdown of journalistic principles that occurred in the past 40 years. Combined, we have a dangerous world of information that has been deliberately falsified in order to appeal to a segment of the population that has chosen to be willfully ignorant.

It seems a contradiction: The more information we have, the more that ignorance is a problem. But to understand why, we have to understand how we make sense of the world.

Making Sense of Our World

Sensemaking is a concept that was first introduced by organizational theorist Karl Weick in the 1970s. The concept has been borrowed by those working in the areas of machine learning and artificial intelligence. At the risk of oversimplification, it provides us a model to help us understand how we “give meaning to our collective experiences.”

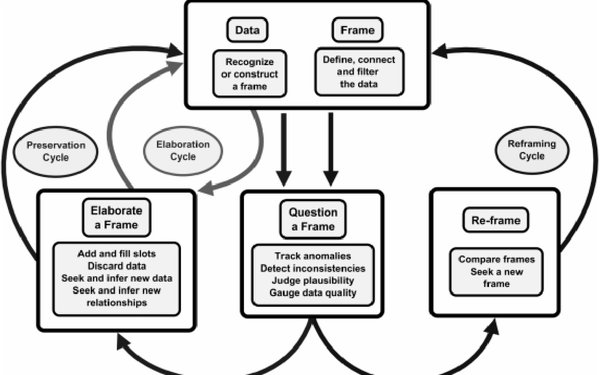

The above diagram (from a 2011 paper by David T. Moore and Robert R. Hoffman) shows the sensemaking process. It starts with a frame — our understanding of what is true about the world. As we get presented with new data, we have to make a choice: Does it fit our frame or doesn’t it?

If it does, we preserve the frame and may elaborate on it, fitting the new data into it. If the data doesn’t support our existing frame, we then have to reframe, building a new frame from scratch.

Our brains loves frames. It’s much less work for the brain to keep a frame than to build a new one. That’s why we tend to stick with our beliefs — another word for a frame — until we’re forced to discard them.

But, as with all human traits, our ways of making sense of our world vary in the population. In the above diagram, some of us are more apt to spend time on the right side of the diagram, more open to reframing and always open to evidence that may cause us to reframe.

That, by the way, is exactly how science is supposed to work. We refer to this capacity as critical thinking: the objective analysis and evaluation of data in order to form a judgment, even if it causes us to have to build a new frame.

Others hold onto their frames for dear life. They go out of their way to ignore data that may cause them to have to discard the frames they hold. This is what I would define as willful ignorance.

It’s misleading to think of this as just being ignorant. That would simply indicate a lack of available data. It’s also misleading to attribute this to a lack of intelligence.

That would be an inability to process the data. With willful ignorance, we’re not talking about either of those things. We are talking about a conscious and deliberate decision to ignore available data. And I don’t believe you can fix that.

We fall into the trap of thinking we can educate, shame or argue people out of being willfully ignorant. We can’t. This post is not intended for the willfully ignorant. They have already ignored it. This is just the way their brains work. It’s part of who they are. Wishing they weren’t this way is about as pointless as wishing they were a world-class pole vaulter, that they were seven feet tall or that their brown eyes were blue.

We have to accept that this situation is not going to change. And that’s what we have to start thinking about. Given that we have willful ignorance in the world, what can we do to minimize its impact?