I have to admit, I’m not a sports fan. And of the few sports I know a little about, European football is certainly not one of them. So my choice to watch the recent Beckham documentary on Netflix is certainly not typical. That said, I did find it a fascinating case study in something I was not expecting: the making and valuation of a personal brand.

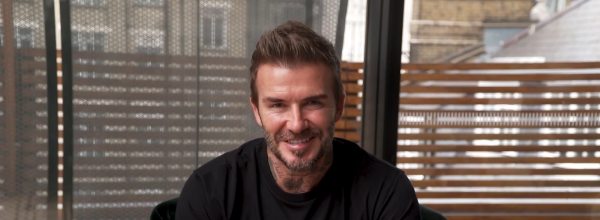

First, a controversial question must be posed: was Beckham a good player? According to those that know much more about the sport than I do, the answer is definitely “Yes” – but he wasn’t the GOAT (Greatest of All Time) – he wasn’t even a GOHT (Greatest of His Time). The closest Beckham ever came to winning the Ballon d’Or, given to the best player of the year, was to place second behind Rivaldo Ferreira in 1999. During his time at Real Madrid CF, he wasn’t even the best player on the team. Granted, it was a stacked team and Beckham was one of the “galácticos” (superstars), along with Figo, Zidane and Ronaldo. But, unlike Beckham, all those other players have at least one Ballon d’Or in their trophy case (Note, fellow Mediapost Jon Last recently took an interesting look at this topic in his column – The Death of Meritocracy in Sports Pay).

But despite this, Beckham was certainly the highest paid player in the world when Timothy Leiweke lured him to LA Galaxy, where his contract also gave him a piece of the profits. So, if he wasn’t the greatest player, but he was the most valuable one, what created that value? Why was David Beckham worth hundreds of millions of dollars?

As the documentary showed, there was a dimension to Beckham’s signing to a team that went far beyond his ability to put a round ball in the net. He was a global brand – the most famous football player in the world. And that’s what Real Madrid president Florentino Pérez and Timothy Leiweke respectively bought when they signed Beckham.

As I said, the documentary revealed some interesting truths about branding. What creates brand value? Who owns that value? What is the price paid for the value of a personal brand?

What the Beckham documentary showed, more than anything, is that brand value is determined in a public market. Beckham certainly brought brand assets to the table: his own athletic ability, being exceedingly good looking, a kaleidoscope of hair styles, and a marriage to one of the most popular pop stars in the world, Victoria Adams – Posh Spice from the Spice Girls. Those were the table stakes for establishing his brand value, the price of entry.

But beyond that, the value of his brand was really whatever the public determined it to be. For example, after he was red-carded in a critical match against Argentina the 1998 World Cup, all of Britain decided that Beckham had cost them the championship. Whether that was true or not (there are a lorry-full of “ifs” in that opinion) it caused his brand value to plummet. There was really nothing Beckham could do. His brand was out of his control. It was owned by the media and public.

The documentary really highlights the viral and frenzied nature of the market that determines the value of a personal brand. And remember, this all took place in the days before social media and the very real impact of being publicly cancelled! Since Beckham’s prime in the 1990s and early 2000’s, the market effect of branding has since been amplified and compressed. The market of public opinion is now wired, meaning network effects happen on incredibly short timelines and without even the illusion of control.

Certainly the monetary benefits of brand usually accrue to the supposed owner of the brand. David and Victoria Beckham are reportedly worth a half billion dollars, making him one of the richest athletes in the world. But the documentary makes it clear that there was a price paid that was not monetary. Much of what we would all call “our lives” had to be traded by the Beckhams for a brand that was controlled by the public and the press. There were no boundaries, no privacy, no refuge from fame.

When we pull back from the story of David and Victoria Beckham, there are takeaways there for anyone attempting to build a brand, whether it be personal or corporate. You may be able to plant the seeds, but after that, everything else is going to be largely out of your control.