If there was one thing that has sparked America’s success, it has been innovation. That has been the engine that has driven the U.S. forward for at least the last several decades. Yes, the U.S. has natural resources. Yes, at one time the U.S. led the world in manufacturing output. But in their pursuit of adding value to economic output to maximize profit, the U.S. has moved beyond resource extraction and manufacturing to the far-right end of the value chain, where the American economic engine relies heavily on innovation.

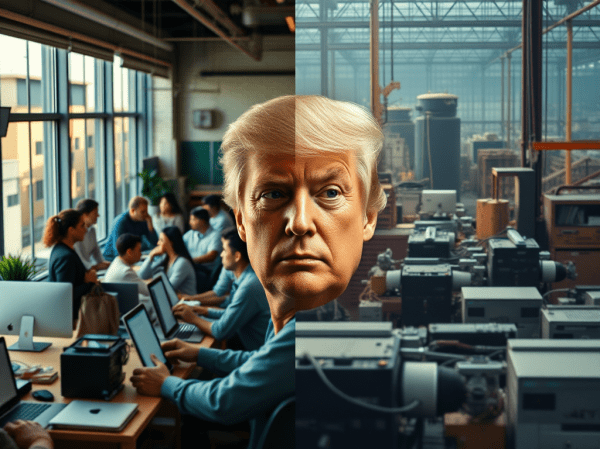

Donald Trump can talk all he wants about making America great again by bringing back manufacturing jobs that have migrated elsewhere in the world (a goal that many, including the Economic Policy Institute, feel is delusion, at least using Trump’s approach), but if innovation dies in the process, the U.S. loses. Game over. It’s innovation that now fuels the American Dream.

Given that, MAGA adherents should be careful what they wish for. The Great America they envision is a place where it may be impossible for that kind of innovation to survive.

World class innovation needs an ecosystem, where there is adequate funding for start-ups, a friendly regulatory framework, a robust research environment and an open-door policy for innovative immigrants from other countries – all of which the US has historically had in spades. And – theoretically at least – it’s an ecosystem that Trump is promising high tech and why the tech broligarchy has been quick to court him. But like so many things with Trump, the reality will fall far short of his promises. In fact, he will likely stop innovation in its tracks and send U.S. ingenuity reeling backwards.

Next to the regulatory and economic inputs required for innovation – and perhaps more important than both – the biggest requirement for innovation is an environment that fosters divergent thinking. Study after study has shown that innovation lives best in an environment that fosters collaboration, invites different perspectives and provides a safe space for experimentation. All those things can be found in exactly the opposite of the direction in which the U.S. is currently headed.

Each year, the World Intellectual Property Organization publishes their Global Innovation Index. In 2024, the U.S. was in third spot, behind Switzerland and Sweden. To understand how innovation flourishes, it’s worth looking at what the most innovative countries have in common. Of the top ten (the others are Singapore, the U.K., South Korea, Finland, Netherlands, Germany and Denmark), almost all score the highest marks from the Economist Democracy Index for the strength of their democracy. Singapore is still struggling towards full democracy, and the U.S. is now considered to be a “flawed democracy”, in real danger of becoming an authoritarian regime.

The European contenders also receive very high marks for their social values and enshrining personal rights and freedoms. Those are exactly the things currently being dismantled in America.

There is only one country which is defined as an authoritarian regime that made the top 25 of the Global Innovation Index. China sits in the 11th spot. This brings us to a good question, “Can innovation happen in an authoritarian regime?” The answer, I believe, is a qualified yes. But it’s innovation we may not recognize, and which may turn out to be a lot less attractive than we thought.

I happened to visit China right around the time that Google was trying to move into the huge Chinese Market. Their main competition was Baidu, the home-grown search engine. I was talking to a Google engineer about how they were competing with Baidu. He said it was almost impossible to match the speed at which they could roll out new features. The reason wasn’t that they were more innovative. It was because they innovated through brute force. They could throw hundreds of programmers at an issue and hard code it at the interface level, rather than take the Western approach of embedding core functionality in the base code in a more elegant and sustainable approach. The Chinese could afford to endlessly code and recode.

It’s Brute Force Innovation that you’ll find in authoritarian regimes and dictatorships. It’s what the Soviets used to compete in the space race. It’s what Nazi Germany used when they developed rocket science in a desperate bid to survive World War II. It is innovation dictated by the regime, innovating in prioritized areas by sheer force despite the fact that the typical underpinnings of innovation – creative freedom, divergent thinking, the security needed to experiment and fail – have been eliminated.

If you look at the playbook Trump seems to be following – akin to the one Victor Orbán used in Hungary (ranked 36th on the Global Innovation Index) or Putin’s Russia (ranked 59th) – there appears to be little hope for the U.S. to retain its world dominance in innovation.