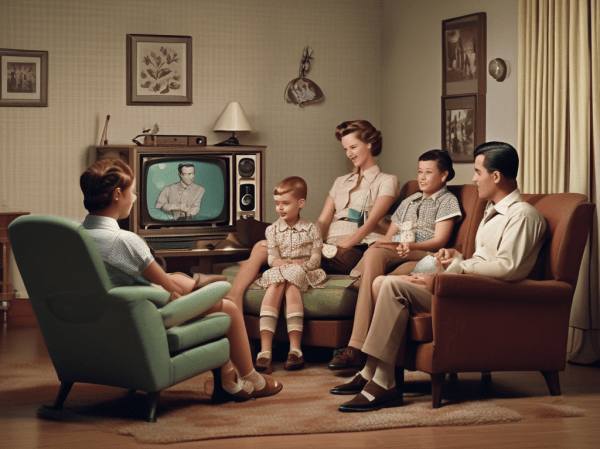

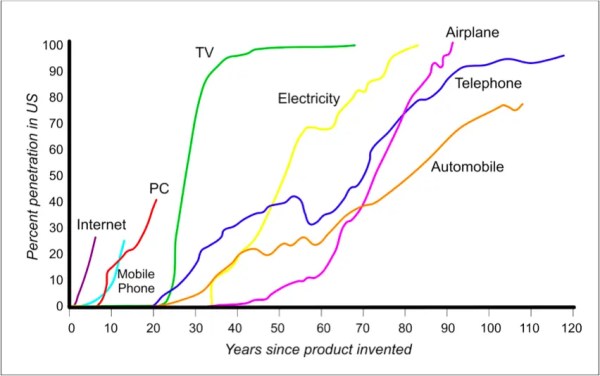

TV viewing, like everything else, has changed drastically in the last few decades. America used to have fairly homogenous tastes in TV. Any given night, it was a safe bet that a significant portion of America was sitting down to watch Happy Days, or All in the Family or, in an early generation, I Love Lucy.

But, with the explosion of the multi-channel universe, our TV tastes have fragmented along several lines. The result? It’s difficult for an advertiser to gain critical mass with an audience by advertising on any one show. America now watches TV in thousands of small splinter segments. And, as we consume more video online, we can pick and choose not just from a broad swath of programming, we can also shift consumption to match out schedule.

This post, however, is not about the challenges of time shifting, market fragmentation or digital consumption. This posts asks a more basic question: what is it about TV that we find entertaining? Why are some shows hits for several seasons, some for a single season, and others complete misses out of the gate? Why do we love the boob tube?

Why We Love TV

Well, the answer, in part, explains the fragmentation of the TV universe. There doesn’t seem to be any universal answer. Humans are too unpredictable to allow Hollywood to forecast with any great accuracy the success of a TV show. There are several different levels on which we can connect with a TV show and the success of any show depends on it’s unique mix of factors that lead to it’s connectability.

TV shows somehow have to weave themselves into the fabric of our society. It becomes a resonating soundboard for our popular culture. This means that the popularly of TV has to not only successfully navigate the churning waters of the diversity of human behaviour but also has to do so against the ever changing snapshot of our cultural context. Obviously, in the 1960’s, the Beverly Hillbillies struck a chord with a significant number of people. It’s unlikely that it would survive today.

In The Psychology of Entertainment Media: Blurring the Lines between Entertainment and Persuasion. (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 2004. Page Number: 275) Cristel Russell, Andrew Norman and Susan Heckler explore the various dimensions of TV “connectedness” and identify just some of the variables at play here. I’ll touch on the more interesting ones.

There are some fundamental truths here when it comes to why we watch TV. At the highest possible levels, there is commonality across all of us. We watch TV to improve our moods, learn something, aspire to a higher place in our society and give us something in common to talk about with our friends and co-workers. But each of those things are much too general to give us much insight into why one show succeeds while another might fail. For example, most sitcoms are funny enough to lift our mood, but some last for 10 seasons and others die shortly after the pilot airs. Simple mood improvement is obviously not enough to explain TV success.

Connecting through the Tube

We start to gain more insight when we look at the level of connection people have with one particular show. The depth of that connection determines loyalty, the degree of social “grease” (how much you talk about a show within your social circle) and, ultimately, the longevity of a show. What is that distinct “something” that causes us to connect with a TV show? On the basis of connectedness, one could argue that, although it only lasted 10 short episodes, Star Trek might be one of the most successful TV shows of all time. It engendered a level of connectiveness that was almost obsessive (remember the backlash when William Shatner told a bunch of Trekkies on Saturday Night Live to “get a life?”). That connectedness created a franchise that spawned 11 movies, 6 TV series and a lifetime slate of speaking gigs (if they want them) for the original cast.

So, what is connectedness? It’s that quality of a TV show that goes beyond simple watching to directly influence the personal and social aspects of our lives. When we connect with a TV show, we seek to jump over the gap that separates us from the show. Russell, Norman and Heckler show that this can happen in three ways:

The Vertical Connection: Viewer to Program

The connection between a viewer and a program is very similar to a brand connection. We become fans of the “brand” of the show. We watch every episode, we feel anxious when we miss an episode, We admire the quality of the production (i.e. the writing) and we may extend our loyalty to the purchase of the show on DVD or perhaps books, soundtracks or other spin offs from the show.

The Horizontal Connection: Viewer to Viewer

Here, shared appreciation for a TV show acts as sort of a “social lubricant.” It gives us common ground for discussion within our social circles. This level of connectedness leads to group watching of a TV show. Often, there are real or aspirational similarities between the cast of the show and these groups of fans. For example, med students love to watch Grey’s Anatomy (and ER before that, and St. Elsewhere before that).

The Vertizontal Connection: Viewer to Character

Here’s where the line between reality and fantasy starts to get disturbingly blurred. Often, fans begin to identify with the cast members in a show, seemingly forgetting that they’re fictional. This combines aspects of the two previous connections. The connection is between the viewer and the show, but it’s a social relationship that goes beyond simple brand-like loyalty. We want to be friends with Ross and Rachel. We want to have Ray Romano as our next door neighbour (preferably without his parents). We want to join the Glee Club at William McKinley High School. We begin to adjust our reality to incorporate the characters fictional reality. This level of connection leads fans to begin adopting gestures, facial expression and vocal characteristics. They want to wear the same clothes, eat the same food and experience the same things.

It’s these three levels of connectedness that account for loyalty to, and through that, the success of a TV show. What leads to these connections?

Growing a Relationship over Time

If you look at the great TV series that have endured over time, they often have one thing in common – few were hits right out of the gate. Cheers, All in the Family, M*A*S*H and many others all took some time to find their audience. And, if we look at our connection to a TV show as a type of relationship, this is not surprising. Relationships don’t suddenly blossom overnight. They take time to develop.

The most successful TV series rely heavily on strong characters. And the series with longevity seem to have characters with some depth and complexity. It takes time to get to know a Hawkeye Pierce, a Sam Malone or even an Archie Bunker. What at first seems to be a one dimensional character reveals more of themselves over time, in a multitude of situations. Strong writing drives this character development. Just like in real life, our strongest TV relationships tend to be with people we’ve known for awhile. Their initial appeal first catches our interest, but there better be some depth there to maintain our interest.

A Continuing Storyline

Just like relationships, a narrative that bridges the gaps from episode to episode seems to lead to greater loyalty. The price of entry is higher (you need to invest in watching a few episodes to pick up the threads that carry from show to show) but once you make the investment, it’s much easier to get hooked.

A personal example shows how powerful this loyalty can be. One of my favorite shows on TV was West Wing. My level of connectedness was primarily between viewer and show – I was awestruck by Aaron Sorkin’s writing. But if ever a TV show required a substantial investment on the part of the viewer, West Wing was it. If you missed an episode or two, the rapid fire dialogue between Toby, C.J. and Josh might has well have been in Mandarin. You had no idea what the hell was going on. I managed to make this investment for the first 3 seasons of West Wing but then lost the storylines somewhere in season 4 and, despite trying a few times, never managed to pick them up again for the rest of the show’s primetime run. Last year, I bought the show in a box set and I’m now working my way through it. The advantage of watching on DVD is that you can always go back to listen to a particular piece of dialogue again.

The Human Connection to the Narrative

A continuing storyline gives us a narrative to follow. And we are huge fans of narratives. We tend to see the world, and even ourselves, through the narrative lens. As I said in a previous post, our brains have a inherent connection to stories. Our brain is built to process a story.

Narratives give us a self view that we use to make sense of the world and our place in it. It provides a frame of reference for the very tricky question of consciousness: Why do we exist? How do we exist? What causes us to act? What causes others to act? Good, evil, God, the Devil, nature, catastrophe, our place in the world – all these questions that we have relentlessly pondered since we were first able to, all have been woven into narratives that form our common mythology. “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely actors.” Shakespeare was on to something, but he had it backwards. The stage is in our minds, a construct of our brain. The script is written by us, and we assign the roles as we see fit, including our own.

If we constantly participate in this ongoing narrative we write of our own lives, deciphering the motivations of others from our vantage point in our own life stories, is it any wonder that we find continuing story lines particularly appealing in our favorite TV shows? This is, as we see it, life. And these story lines bring the characters alive (sometimes too alive) for us.

Why We Love Happy Endings

If we see life as a story, it makes sense that we’re suckers for a happy ending. Aristotle figured this out about humans 2000 years ago. ” A good man must not be seen passing from happiness to misery,” and “a bad man from misery to happiness.” Narratives have to make sense to us, based on our understanding of what is right or wrong. In other words, shit happens, but don’t let it happen in my favorite TV show. Of course, script writers use our inherent dislike of this moral unfairness to tweak us on a regular basis. But in doing so, they run the risk of losing us. After getting hooked on an entire season of 24, I was so upset at the resolution of season 1 that I never watched it again. I had the same reaction when Mark Green died in ER. There are consequences if you decide to break Aristotle’s laws of narrative.

Tomorrow, I’ll further explore how we connect with TV. For example, I’ll look at why women tend to accept fictional characters at face value, while men remain more detached, treating characters as a literary device to be manipulated by the author. Why teenagers in particular are susceptible to being influenced by characters in TV shows. Why some of us go “over the edge” in our degree of “fan-ship”. And why some of us love action packed shows and others like to relax with more sedate shows.

I’ve

I’ve  On Monday, I talked about the normal distribution of variance in any human characteristic, typically plotted on a bell curve. Our need to seek sensation is just such a trait. Some of us are quite content to keep our pulse ticking away at a rate barely above comatose. Some of us constantly seek a massive jolt of adrenaline, always riding the ragged edge of disaster. Most of us fall somewhere in between. Marvin Zuckerman

On Monday, I talked about the normal distribution of variance in any human characteristic, typically plotted on a bell curve. Our need to seek sensation is just such a trait. Some of us are quite content to keep our pulse ticking away at a rate barely above comatose. Some of us constantly seek a massive jolt of adrenaline, always riding the ragged edge of disaster. Most of us fall somewhere in between. Marvin Zuckerman

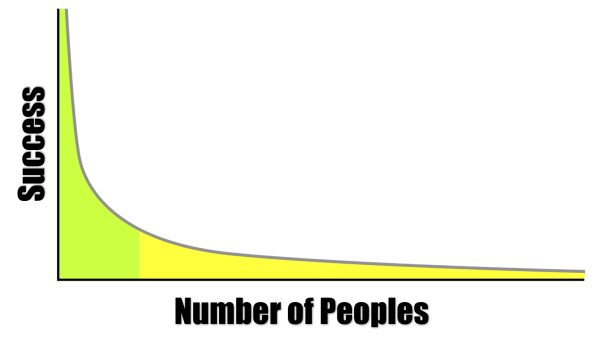

This variation typically plays out in a normal distribution curve, more commonly known as a bell curve. Most of us cluster towards the center – the norm. And as we move out from the center, venturing one or two standard deviations from the norm into outlier territory, our numbers drop dramatically.

This variation typically plays out in a normal distribution curve, more commonly known as a bell curve. Most of us cluster towards the center – the norm. And as we move out from the center, venturing one or two standard deviations from the norm into outlier territory, our numbers drop dramatically.