In Brock and Livingston’s investigations of our need for entertainment, they ran up against a problem: how do you define entertainment? In attempting to answer that question (at least for the purpose of their study), they uncovered an interesting finding that provides some troubling commentary for our society.

Watching vs. Doing: The Evolution of Entertainment

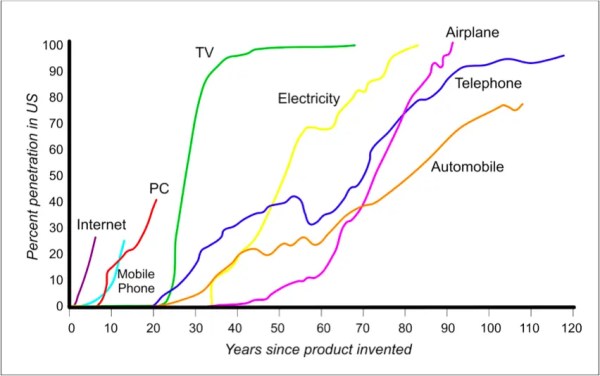

Brock and Livingston were seeking to separate passive entertainment (watching TV) from active entertainment (playing a sport). They asked study participants to further define what they meant when they used the word entertainment. In two separate groups, 3 out of 4 participants defined entertainment in it’s passive sense – sitting down to watch a TV show or movie. Now, perhaps this is just a question of semantics – the word “entertainment” and the word “activity” may seem to have different meanings for us. But there are reams of social data to show that as we have adopted more forms of passive entertainment, the most ubiquitous being television, our level of activity has steadily dropped. This, however, is not the only fall out of our addiction to TV.

Watching vs Belonging: The Erosion of Social Capital

I’ve talked before about Robert Putnam’s book Bowling Alone, the Collapse and Revival of American Community. Putnam investigated a dramatic reversal in our desire to engage in community minded activities that occurred in the mid-60’s. These activities ran the gamut from voting and being active in PTA’s to having friends over for a card game and joining a bowling league. In chart after chart, Putnam showed how this community-mindedness peaked in the late 50’s and early 60’s and then went into a long and steady decline over the last half century. As TV invaded our front rooms, we abandoned the community hall, the voting booth and the local chapter of The Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks (one of the biggest fraternal organizations in the world). We stopped spending time with each other. Our definition of entertainment moved from the active to the passive.

I’ve talked before about Robert Putnam’s book Bowling Alone, the Collapse and Revival of American Community. Putnam investigated a dramatic reversal in our desire to engage in community minded activities that occurred in the mid-60’s. These activities ran the gamut from voting and being active in PTA’s to having friends over for a card game and joining a bowling league. In chart after chart, Putnam showed how this community-mindedness peaked in the late 50’s and early 60’s and then went into a long and steady decline over the last half century. As TV invaded our front rooms, we abandoned the community hall, the voting booth and the local chapter of The Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks (one of the biggest fraternal organizations in the world). We stopped spending time with each other. Our definition of entertainment moved from the active to the passive.

This expectation to be passively entertained has spilled into other areas of our society as well. How we perceive our world may have changed from an environment we interact with to a parade that we simply sit back and watch go by. Neil Postman, in his book Amusing Ourselves to Death, speculates that as America turned from a culture revolving around the printed word to one revolving around images (especially images that jump cut from one to the other, set to a pounding aural beat, saturated with high impact stimuli like violence and sex) we have become a society of attention deficit watchers that have high expectations of being passively entertained, no matter where we are:

What I am claiming here is not that television is entertaining but that it has made entertainment itself the natural format for the representation of all experience. … The problem is not that television presents us with entertaining subject matter but that all subject matter is presented as entertaining, which is another issue altogether.

This trend shows up in our consumption of news, political issues and education. Classrooms now are not the Socratic arena of debate so much as they are a theatre, where the professor or lecturer is expected to entertain with a bag of tricks including animated Powerpoint presentations and multimedia content. Consider the difference in the campaigns of two politicians from Illinois. In 1858, debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglass took 7 hours and the entire audience stayed put in the hall, their butts glued to hard wooden chairs for the entire time (the bladder control alone boggles the mind). 151 years later, we had trouble making it all the way through a 37 minute YouTube video of a Barack Obama speech.

A Different Definition of Thrill Seeking

On Monday, I talked about the normal distribution of variance in any human characteristic, typically plotted on a bell curve. Our need to seek sensation is just such a trait. Some of us are quite content to keep our pulse ticking away at a rate barely above comatose. Some of us constantly seek a massive jolt of adrenaline, always riding the ragged edge of disaster. Most of us fall somewhere in between. Marvin Zuckerman created a scale that measured our need for sensation back in 1971.

On Monday, I talked about the normal distribution of variance in any human characteristic, typically plotted on a bell curve. Our need to seek sensation is just such a trait. Some of us are quite content to keep our pulse ticking away at a rate barely above comatose. Some of us constantly seek a massive jolt of adrenaline, always riding the ragged edge of disaster. Most of us fall somewhere in between. Marvin Zuckerman created a scale that measured our need for sensation back in 1971.

This need for sensation has an impact on the type of entertainment we seek. Historically, one would expect a strong correlation between our need for sensation and our level of activity. Traditionally, the need for sensational thrills was satisfied through participation in high adrenaline sports and activities such as rock climbing, various forms of racing and other “extreme” pursuits. The neurological loop here is fairly easy to understand. By pushing our bodies to the point where our brain decided we were in danger, our neurological defence mechanisms were duped into taking the appropriate response: a massive release of neuro-chemicals, including adrenaline, that jolted our body into a higher state of awareness and readiness. The seeking of sensation provided a natural high. On the upper end of Zuckerman’s scale, extreme sensation seeking can be clinically addictive.

But technology has thrown us a psychological curve ball when it comes to sensation seeking. There used to be a fairly well defined divide between most forms of passive entertainment and sensation seeking. The exceptions were gory spectacles such as the gladiators of ancient Rome and, in more recent times, wrestling and boxing. However, the line between the two has become more and more blurred in the 20th century. Passive entertainment now regularly relies on unabashed tweaking of our inherent subliminal defense, retaliation and sexual modules. Modern entertainment plays directly to our animal instincts.

This is where we get an especially grim view of our future. Yesterday, I mentioned that Robert Kubey and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi found evidence that TV was addictive, in the true biological sense of addiction. Sensation seeking also has found to be physically addictive. Are we becoming a nation of passive voyeurs that only truly become alive when we’re plugged into the entertainment grid? Suddenly, the premise of The Matrix doesn’t seem that far fetched (ironic, considering the movie series was a perfect example of sensation seeking through passive entertainment).

The modern video game raises this ambiguity between sensation seeking and passive entertainment to a new high (or low, depending on your perspective). Through lifelike graphics and the game producer’s mastery of what appeals to our baser instincts, video games now efficiently deliver high octane jolts that we used to have to get by actually doing something. What does this mash up of passive entertainment and sensation seeking mean for marketers in the future?

That, alas, is a topic for a future post.

What about the stimulation of watching something like the Olympics that encouraged many people to join athletics clubs . Watching marathons on tv that encouraged many thousands to start running and join clubs. Surely that shows that watching others can stimulate some to do the same